Hunting

Aw, Duck: Reduced Fall Waterfowl Flight Forecasted

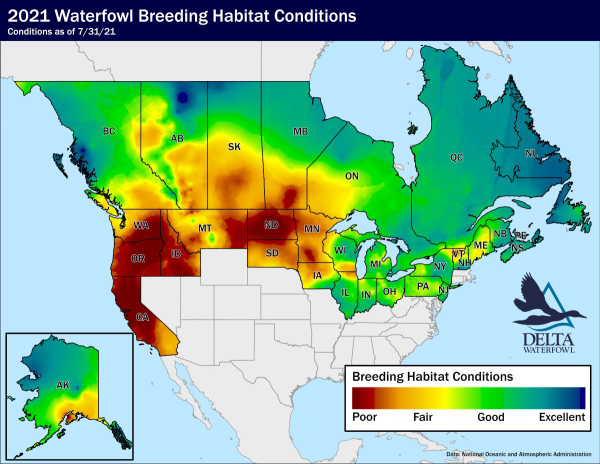

Delta Waterfowl forecasts that poor breeding conditions in the prairie pothole region will result in a smaller fall flight than waterfowl hunters have experienced for many seasons. The Duck Hunters Organization expects that while blue-winged teal, green-winged teal and gadwalls had average to below-average production, other key species fared worse, including mallards and, even more so, pintails, wigeon and canvasbacks. However, favorable conditions were available to eastern-breeding ducks — essential to the Atlantic Flyway — and to boreal-nesting species such as bluebills and ring-necked ducks.

“This is a unique year in that the prairie pothole region — the most important duck production area on the planet — is almost universally dry,” said Dr. Frank Rohwer, president and chief scientist of Delta Waterfowl. “A lot of the prairies were dry the past two springs as well, but at least there were pockets of areas with good wetland conditions. But this year we likely had poor duck production due to many birds overflying the prairies, and those that stayed showed reduced renesting effort and low brood survival. There will be far fewer juveniles in the fall flight, and that’s unfortunate because the best seasons are always those when you’ve got an abundance of young ducks winging south.”

Delta’s analysis is delivered despite the second-straight Covid-related cancellation of the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey — a key barometer of the fall flight that’s otherwise been conducted annually since 1955 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service.

State surveys were, however, successfully conducted by wildlife departments in North Dakota, Michigan, Wisconsin and Oregon. Nowhere were drought conditions more evident than in North Dakota, a critical duck producing region for the Mississippi and Central flyways. The North Dakota Game and Fish Department estimated an 80 percent decline in wetlands from 2020, and the breeding duck estimate of 2.9 million marks a 26.9 percent drop from last year.

“North Dakota’s survey is the bad news we knew was coming,” Rohwer said. “The reduction in water is staggering. It’s the highest percentage decrease in the history of the North Dakota survey.”

Still, there are silver linings to be found when small, shallow prairie wetlands — those most vital to making ducks — dry out. Little precipitation fell throughout the winter and early spring, and in turn the normally wet pools produced abundant vegetation.

“The drought cycle rejuvenates wetlands with food for hens and ducklings in the following spring,” Rohwer said. “Assuming we have better water next year, ducks will rebound quickly. We could have outstanding duck production.”

Carryover ducks from consistent years of good production also means that populations of adult, breeding ducks — though far more challenging to decoy — remain high. Despite indicating a significant decrease from 2020, North Dakota’s breeding-duck estimate remains 19 percent above the long-term average. And long-term data indicates that most duck populations are well above average — including a 2019 estimate of 38.9 million breeding ducks, 10 percent above average.

“It’s going to be a tough year, but the good news is duck numbers remain relatively high,” Rohwer said. “This isn’t like 1992 when we entered a drought and the bottom had already fallen out in terms of breeding populations. And one of the things about a drought is you get better hen survival in the summer, because their nesting efforts are weaker and therefore they are less vulnerable to predators.”

Delta expects that mallards had poor production.

“Mallards are great renesters — one of the key reasons they’re such prolific ducks is if one, two or even three or more nests fail, they’ll try again — but that isn’t going to be the case this year,” Rohwer said. “Wetland resources that drive renesting were not available.”

Blue-winged teal, Delta believes, had a decent production year relative to other ducks. While they tend to attempt only one nest, they do so sooner than most species, in late April and early May — a period in which a smattering of wetlands was still available in their core breeding range across the Dakotas.

“Anecdotally, as I’ve driven across the prairies I’ve been impressed that there are way more bluewing broods than I expected,” Rohwer said. “For ducks that rarely renest following nest destruction, drought has less of an impact.”

Green-winged teal nest farther north in the upper tier of the Canadian parklands and the boreal forest, where wetland conditions fluctuate far less year to year. Delta forecasts that their production was stable.

“I think teal hunting should be better than anything else,” Rohwer said. “Mallards and gadwalls will be a decent second.”

Interestingly, the North Dakota survey indicated that the seemingly unflappable gadwall population continues to boom, increasing 47.4 percent to 649,216 ducks — an incredible 109.5 percent above the long-term average.

“Gadwalls are challenging to predict,” Rohwer said. “I suspect they did better than mallards because they’re less dependent on renesting. However, they also tend to nest late — as far as into early June — and that’s when wetland conditions really deteriorated. They’ve definitely proven a very resilient species.”

The news is especially unfavorable for pintails, as conditions were very poor in prairie Saskatchewan — the traditional heart of the pintail’s breeding range — and the shallow wetlands that pintails especially depend on were nowhere to be found.

“Pintails especially took it on the chin this year,” Rohwer said. “A drought is not what we needed to get sprigs back on track.”

Delta believes that wigeon, which also have the core of their breeding range in Saskatchewan, did not fare well either in that exceptionally dry part of the prairies.

A decreased fall flight of canvasbacks is predicted as well, due to poor nesting conditions in the parklands of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and indirectly, the Dakotas.

“Not only were conditions poor in the canvasback’s preferred breeding range in the parklands, but I suspect a greater abundance of redheads flew north into that same range due to the dry Dakotas,” Rohwer said. “There’s some disagreement among scientists, but I believe that in years when the prairies are dry, there’s greater nest parasitism — redheads laying their eggs in canvasback nests — which causes canvasback eggs to be inadvertently kicked into the water or buried beneath the surface within the nest. And, like mallards, I expect this to be a one-and-done nesting year for cans.”

Redheads have been steadily increasing for a number of years, but Delta believes this year’s conditions will result in a short-term reversal of that trend. Those that nested in the Canadian parklands likely did fine, but prairie-nesting redheads faced dry conditions.

“My guess is we’ll see a big dip in redhead numbers in the 2022 survey,” Rohwer said.

Production of bluebills was likely consistent with recent years this spring.

“Lesser scaup nest in the uplands, which is unique among divers,” Rohwer said. “They probably didn’t have a great year because they partially depend on the prairies, but given that a number of lessers and the majority of greater scaup nest in the boreal, I suspect they’ll be less affected by the drought than most ducks. That said, their production in the boreal has been lousy in recent years — I suspect due to increasing predator populations.”

A close relative of bluebills, ring-necked ducks are expected to have furthered their upward-trending population this spring.

“Ringnecks are going to have another good year breeding in the stable boreal,” Rohwer said. “They’re also spreading south from the western boreal forest, in normal years finding relatively stable water conditions in the Canadian parklands and replacing bluebills big time. And unlike bluebills, ringers nest over water, where they appear to be more successful at hatching nests.”

In the Pacific Flyway, drought conditions swept California, Oregon, British Columbia and most — but not all — of Alberta.

“In the west I have nothing good to report,” Rohwer said. “If you’ve watched the news at all you know that it’s experiencing disastrous heat, drought and fires. That’s not a recipe for good duck production. And in California we know that upwards of 70 percent of the mallards harvested are typically hatched within the state. That won’t be the case this year, because many wetlands were bone dry and produced nothing.”

The one bright spot is the stable conditions of Alaska, which should add a number of green-winged teal, pintails and wigeon to the Pacific’s fall flight.

The news is better on the other side of the continent: Excellent breeding conditions were observed in eastern Canada, which Delta believes fueled strong production of Atlantic Flyway mallards. Good nesting conditions were also present for black ducks, ring-necked ducks and wood ducks.

“Atlantic Flyway hunters should have a better season than folks farther west relative to recent seasons,” Rohwer said. “Conditions in the northeast United States were average, and eastern Canada was quite wet.”

While the flight forecast is less promising than in recent years, Delta Waterfowl encourages hunters to oil their shotguns, tune their calls and get ready: This remains a wonderful era to be a duck hunter.

“There are still plenty of ducks, and we feel the liberal regulations in place for the coming season are entirely appropriate,” Rohwer said. “Hunting has little to no effect on the ebb and flow of breeding duck populations, because primarily we shoot juveniles. Low duck production is likely to result in challenging hunting, but the idea you shouldn’t hunt — whether you fear harming duck populations or experiencing a lack of success — is absurd. Weather events such as cold and precipitation have just as much an effect on hunter success, and I’m confident plenty of people will have good seasons.”